Market Update - Part 2

The effect of a low interest rate economy

The Coronavirus has taken the headlines and perhaps rightly so. However, the longer-term issue that as investors we need to understand is that we are currently stuck in an ultra-low interest rate environment and that this continues to affect the economy in ways that traditional textbooks could not have predicted.

It is useful to remind ourselves of the role of interest rates to the broader economy. Interest rates set by central banks influence the cost of borrowing and returns on our savings - lower rates are bad for savers and good for borrowers and vice versa.

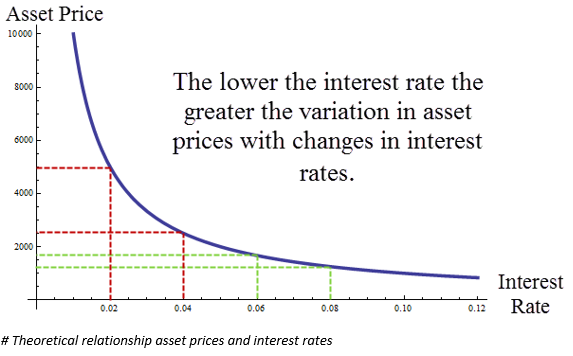

However, long-term rates have a material impact on asset valuations and these rates have never been so low. The reason valuations are affected in finance terms is “the discount rate” but in layman’s terms it is simply accounting for the time value of money.

To demonstrate this relationship, it might be easier to work through a simple scenario. What is a future cashflow worth? Well $100 in one years-time if rates are 10% is worth $90.91 today i.e. $90.91 invested @10% today will give you $100 in one years-time. If rates were 5% that number increases to $95.24 and 1% to $99.01.

But businesses (should) produce cashflows for a long time. So, what is 20 years of cashflows of $100 per year worth today? Well if interest rates were 10% - $851, at 5% they would be worth $1,246 and at 1% $1,805.

Whilst this is a theoretical graph and a theoretical scenario it is worth recapping what Australia’s interest rates have done over the past 30 years and reflect on why asset prices have risen so strongly over the same period. The 10-year bond rate (plus a risk premium) is a standard measure used to discount future cash flows and is also the predictor of future cash rate. At the beginning of 1990, the time of the last Australian recession, the 10-year bond rate was in the region of 14%. The RBA cash rate was sitting at 17.5%. Inflation as measured by Consumer Price Index as at March 1990 was 8.6% consistent with the average of the previous decade.

In today’s environment these numbers will illicit very different emotions to parts of the community. If you are retired and looking for an income stream you might be keen to see a cash rate at 17%, however if you are an average borrower in Australia this rate would simply be impossible to service.

Interest rates provide the tools to value all assets, however in the current environment this theoretical relationship between interest rates and asset prices becomes interesting because mathematically when the discount rate hits zero, the time value of money relationship breaks down.

It is also true to suggest that the change in asset price is much higher when interest rates are low. For example, the change in the interest rate moving from say 17% to 15% will result in a much smaller change in the asset price than an interest rate move from 3% to 1%.

The concept of negative interest rates brings a whole new level of complexity into valuations. Whilst we will not elaborate further on the topic in this newsletter perhaps you can spare a thought for German investors where earlier this month a 30-year German Bund traded at (minus) -0.148%.

Investors’ response

As interest rates have reduced, investors have gone searching for yield (income) bidding up the prices of any asset that can demonstrate an income stream. We have seen heavy demand for any assets that provide income higher than the current sub 1% cash rate. Investors have discounted the inherent risk in these assets or in some cases simply disregarded the concept of risk altogether.

All asset classes have been bid up in an attempt to secure some level of income, including debt, equities and property. We are, and should expect to see, increased levels of volatility when very high valuations are exposed to an exogenous shock such as we are seeing with the coronavirus.

While it is trite to play down the concern of a viral pandemic, Shane Oliver has recently published an article highlighting some of the other worries that we have experienced just in the past 5 years that created volatility and investor concern: deflation; commodity/oil crash; Grexit; China worries; Brazil and Russia in recession; manufacturing slump globally; Fed rate hikes; Brexit; South China Sea tensions; Trump; Eurozone elections; North Korea; Germany; Catalonia; Italy; US inflation and rates; Trade war; China slowdown; Aust Royal Commission; Aust housing downturn; US government shutdown; inverted yield curves; impeachment; Aust recession fears; and Iran tensions.

All of these issues were concerning at the time simply because they all represented unknown factors. Unknowns create fear in investment markets as we are currently seeing.

What should investors do?

We need to recognise that whilst market volatility isn’t comfortable, it is normal and it’s the price investors pay for higher long-term returns. The largest mistakes investors can make is letting their short-term concerns excessively influence long term decisions. Whilst we encourage investors to remain aware of current events and how they may impact your investments, tracking them daily provides little benefit.

Trusting the longer-term outcome of an actively managed, diversified investment strategy will reduce short term investment anxiety.